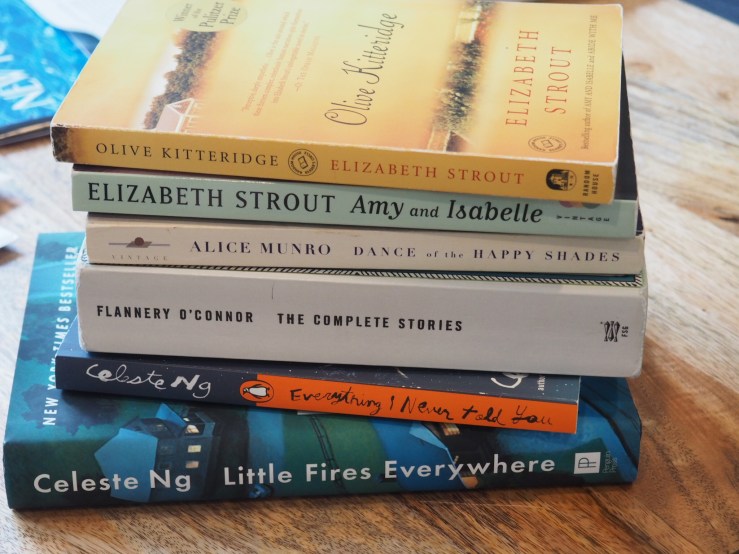

July means summer. And summer means reading. Since I have been more purposeful in my writing and finding time to write, I’ve been thinking more about the writers who have been most influential and inspirational to me.

Elizabeth Strout: Olive Kitteridge; Amy and Isabelle

Linked short stories. Ever since I read Olive Kitteridge, I keep coming back to the idea of linked short stories. She showed how it’s possible to serve as a witness to a character and a narrative arc without having to follow that character’s POV closely all the time. In fact, the story turns out to be as much about the town itself and the rest of the people in it as it does about Olive. Elizabeth Strout wasn’t the first person to teach me this lesson, but she really taught me that you could use short stories and many, many characters’ POVs, to tell a story.

Also, Amy and Isabelle. The mother-daughter relationship, the imperfections of their relationship, the small town, the scandal of being in love with a teacher, the scandal of teenage pregnancy, the scandal of a missing little girl (I was reading this book right about the time that the scandal of “Baby Doe”/ Bella Bond was happening in the Boston area), the inability of the characters to put thoughts and feelings into words. In her novel, even, she switches POV around every now and then, so she’s close to Amy and then to Isabelle and then a woman in the grocery store for only a moment and then to Isabelle’s co-workers. Instead of making it confusing or hard to follow, that small shift in POV seems to make the story even more rich, seems to give the situation a few more layers, more vantage points. It’s not just the one town’s person or one character that we see, but the more that we see, the more complex the place, and the story, become.

I took a course on novel writing through an organization called Grub Street. One of the aspects of craft that we discussed was the idea of the emotional center. Amy and Isabelle has a beautiful emotional center. It is the center of all the tension, where Isabelle believes that her daughter’s beauty is to blame for all that has happened to her and she cuts her daughter’s hair off. All of it. The moment is incredibly tense. And incredibly emotional. It’s not the climax of the whole story, but it carries enough weight itself, and it gets at the heart of the problem between Amy and Isabelle. An explosion of tension.

Alice Munro: “Walker Brothers Cowboy,” from Dance of the Happy Shades.

This story is set in the 1930s in Canada. It is summer. It is hot. Everyone is poor. The story is told from the point of view of the daughter, a young girl. The father is a happy man, always joking around, the same in every situation. The mother “has headaches.” She makes the daughter stand for dress fittings, something the daughter despises. “She is not able to keep from mentioning those days” – the days that are past when she (and her husband and daughter) was happier. This story puts two women opposite one another. The mother – Ben’s wife, and Nora – a woman Ben used to see. When we meet Nora, she is distinctly different from the mother. She has and drinks whisky (“One of the things my mother has told me in our talks together is that my father never drinks whisky. But I see that he does.”) She dances. She laughs at all Ben’s stories and songs. She is very different from the daughter’s mother – Ben’s wife. We see it all through the actions and dialogue that the daughter shares.

And then they have to leave Nora’s house, go home to the mother. In the car, “my father does not say anything to me about not mentioning things at home, but I know, just from the thoughtfulness, the pause when he passes the licorice, that there are things not to be mentioned. The whisky. Maybe the dancing.” Although the girl does not consciously seem to know that this woman once had a relationship with her father, we see that in the way that the girl sees them interact, in the details that Alice Munro shares through the girl’s eyes. Even though, at the end, she still can’t articulate the nature of Ben and Nora’s relationship, she does share something else that she has learned from the interaction – that there are things that should not be mentioned to her mother. I love the sense that Alice Munro seems to have told this whole story in order to arrive at this one, simple realization, even though, there are so many facets to the story, and the father clearly had a relationship of sorts, in some other facet of his life, with Nora.

Celeste Ng: Everything I Never Told You

In the same Grub Street class I mentioned earlier, a segment of the class focused on “getting the outside in” to your story. Ways that you can use events outside the direct narrative of the story to reflect some aspect of, or tension in, the story. There are moments in Everything I Never Told You where Celeste Ng does this beautifully, seamlessly. She shows us what the 1970s really felt like for Lydia’s family, a multi-racial family living in Ohio. She shows us the current events, the immediate effect that Loving v. Virginia had on them: James, a Chinese-American man, and Marilyn, his white wife.

“Just days before, hundreds of miles away, another couple had married, too – a white man, a black woman, who would share the most appropriate name: Loving. In four months, they would be arrested in Virginia, the law reminding them that Almighty God had never intended white, black, yellow, and red to mix, that there should be no mongrel citizens, no obliteration of racial pride. It would be four years before they protested, and four years more before the people around them would, too. Some, like Marilyn’s mother, never would.”

There are many ways that a family has problems. This is just one way, one way that the problems begin for this couple, and they have no control over it. This mention of something national helps us to understand some of the problems that the family faces, especially if we are familiar with this particular court case.

In another instance, Celeste Ng makes sure we remember we are in the 1960s and 1970s with a broad sweeping paragraph covering the passage of time.

“Ten years later it had still not come undone. Years passed. Boys went to war; men went to the moon; presidents arrived and resigned and departed. All over the country, in Detroit and Washington and New York, crowds roiled in the streets, angry about everything. All over the world, nations splintered and cracked: North Vietnam, East

Berlin, Bangladesh. Everywhere things came undone. But for the Lees, that knot persisted and tightened, as if Lydia bound them all together.”

We know about this time. We know about going to the moon. The presidents. Maybe we know about the riots. (We probably do now that we are, once again, a Nation focused on protests.) And because we know all these things – allusions – we understand the turmoil that the family is going through. The outside world comes into this very intimate story of a family and helps to tell it.