Since moving closer to home, my mother does what mothers do with their adult children who finally have places of their own, places that they are likely not leaving very soon, and she encourages me to take the things that are mine, or to help her get rid of the things that are mine and that I don’t want anymore. I did this with my books some years ago: pulled books off of the shelves in my childhood room and stacked them on the floor. So many small towers of books covered the floor that it was difficult to walk. Among the books that I stacked and donated were a number of translations of classical texts that I thought I wouldn’t need ever again. I had given up on Ancient Greek, afterall, and I never really liked the Odyssey, and I’d never read the Iliad. I kept my copies of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I kept a small collection of autographed books and I kept the historical fiction books by Ann Rinaldi that really got me to like reading when I was 12 or 13 years old. My mother and I donated the books and I didn’t actually think about them again.

Since moving in with my wife, our bookshelves have always been full. I try to go through the shelves once a year, collect a few to donate or to leave in Little Free Libraries around the city. In our first house together, Jen built me beautiful bookshelves. I culled my collection when I banished the Ikea shelves we’d started out with and still somehow managed to fill all the new shelves. I sifted through them again when we left Massachusetts. In fact, we moved to Atlanta without a bookshelf. I put some of my favorite books into one box and labeled them “Essentials,” thinking that if I had to put the others into storage, I could live with those. But then, we couldn’t stand to look at the boxes anymore and we unpacked them. We stacked the books against the bedroom wall in our apartment, shoved them into haphazard groups. It was impossible to find anything and we tripped over the piles on a regular basis.

The last book that I read in 2020 was Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey. It took me a few days to get through the hundred-pages of introductory materials, and two things from Wilson’s “Translator’s Note” stuck with me. First, she writes that “all modern translations of ancient texts exist in a time, a place, and a language that are entirely alien from those of the original” (Wilson, 87). Even as ancient texts exist in times, places, and languages far from our present day, the fact that they do exist at all is magical to me. Even as they exist now, they also existed thousands of years ago in their own situations. These considerations must be addressed on a continuum, taking each piece into consideration, swinging back and forth, letting each piece influence and be a part of the next. Then, at the very end of the “Translator’s Note,” Wilson presents a scenario: a stranger comes to us, tells us stories, and asks for shelter (Wilson, 91). What would we do? Would we welcome them? Turn them away? Would we listen to the story? These rhetorical questions, this scenario, of strangers coming into our country with stories and experiences and lives that are different from our own felt poignant. In our reality, we were turning those people away. Aside from Odysseus being Odysseus (I honestly don’t know if I would put up with the man), I thought that this appeal to the contemporary audience, imagining Odysseus as a refugee, a soldier with PTSD, was one way to make this story relevant, to help people today see how the story might have some impact on our current situation.

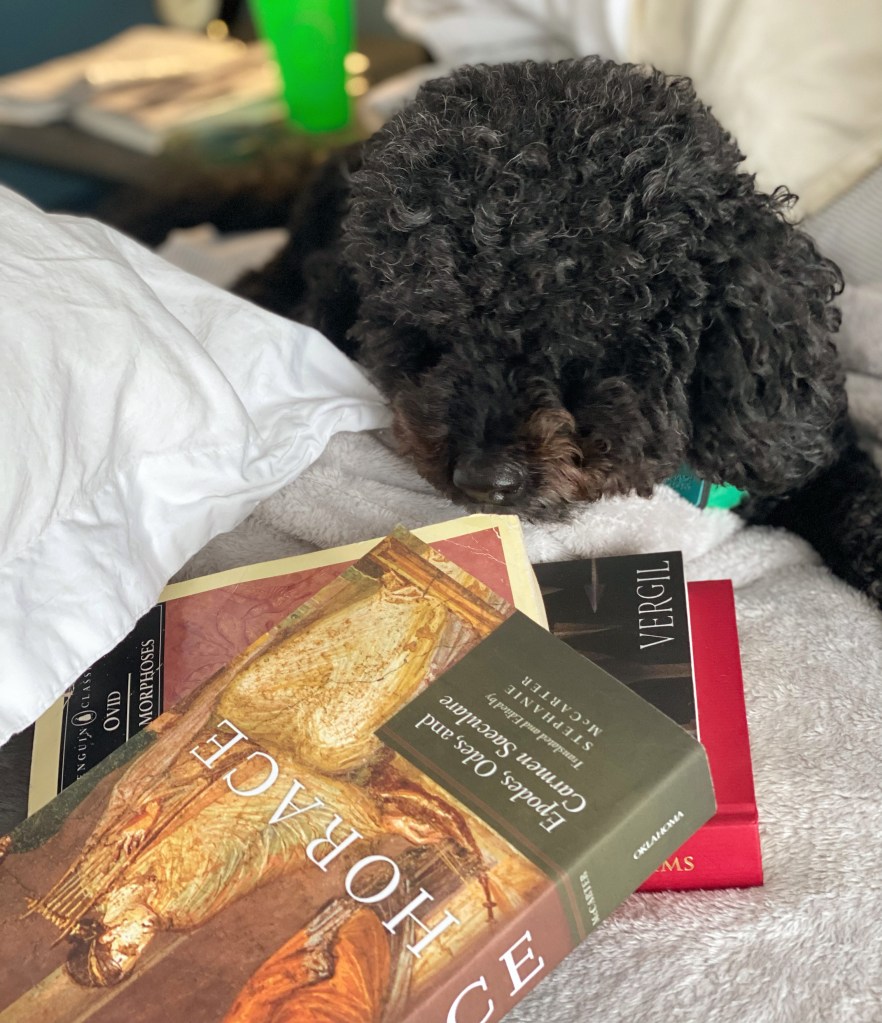

I mulled all of this over, wondering if there was, in fact, something there that I could write about. I texted my mother and asked if she could look for my old translations of the Odyssey, the Iliad, the Metamorphoses, any of those old epics. She texted me back a picture of a single Latin reader for Ovid (from my sophomore year at Mount Holyoke). That was all that was left. I’d hoped that perhaps they were up there hiding next to the binder that I used for Ancient Greek, that I hadn’t really gotten rid of them. But they were gone. So, I bought them again. I told my advisor the short version of this story when I asked the question: “so, do you think I could write a dissertation about this?” He, matter-of-factly, advised me never to throw out that which might be useful later. This is already bad news for my wife, as the new books are on our shelves, and the collection is growing, most recently marked by two versions of Sarah Ruden’s translation of The Aeneid (one from 2008, and the revised edition from 2021).

Every time I go home, I look through the bookshelves, to see if there is anything I want to take with me. On my last trip home at the end of June, hidden away in the family room, I found my first copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. My high school Latin teacher had given it to me on some occasion I can’t remember, and it was the translation she read to us from on Fridays in the Introduction to Latin class for eighth graders. I flipped it open to the first page and the translator of this version of the text is Mary Innes, the only woman to translate the entire Metamorphoses into English (although this will change soon). Even while many classicists are trying to rescue, recover, and (re)inscribe those women writers in Latin and Greek, it seems just as important to build my collection of classics in translation starting with women translators. It seems just as important because it is. Translation is just one way to be involved in classics, to use ancient languages, and it is one way that makes those stories and texts more accessible to those that don’t have the language. Perhaps this is why it is so important. Not that these translations have the last word, but they show one way for women to be involved in the field, even as they show different ways to interpret and engage with these ancient texts, ways that these texts are still relevant.